Letters from the Future (of Learning): With Generative A.I., We are Frogs in the Pot

Whether the story of the frog in the pot is true or not, one thing seems clear:

We homo sapiens are the ones being cooked -- slowly, inexorably -- even though our insistence on pretending otherwise stubbornly persists.

Case in point: the major story in education this week is all about the latest NAEP scores in reading and math, and how they are the lowest in decades. “These results show that there are troubling gaps in the basic skills of these students,” said Peggy Carr, commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, which gives the NAEP exam. “This is a huge-scale challenge that faces the nation.”

Sure. And yet, no.

It’s not that literacy and numeracy don’t matter. It’s that while we slept, the whole foundation of education (or at least the way we have designed and structured it up to now) has become fossilized.

Yes, I am talking about generative A.I.

Yes, it really is that disruptive.

(And yes, I did try to warn you in 2014.)

As Technology professor Alec Couros put it last week at a conference about the future of AI in education, “A.I. will not take your job. But a person using A.I. will.”

To which I say: for now -- until a newer version of A.I. decides it’s ready to just rely on itself.

So we have bigger fish to fry than NAEP — and bigger problems than basic skills.

The whole landscape of our relationship to knowledge -- from access to application -- is changing by the minute. And this is happening in just about every imaginable field.

Right now, for example, I can say confidently I am a better writer than the large language models out there, from ChatGPT to Perplexity.

I am equally confident that this technology will surpass me sooner rather than later.

What then?

Similarly, I’ve been mesmerized by the sorts of images Dall-E and Midjourney can create -- especially the images my friend Anne Paris has been generating as a way to literally visualize her dreams (check them out below). And when I made my friend Ross Peters aware of this entirely new well-paying career -- prompt engineer -- he rightly noted that the need for a human to skillfully craft the right sort of prompt to yield the best possible results from A.I. is really helpful now -- and will probably cease being so entirely in a matter of months.

In the face of such daunting upheavals, NAEP scores provide something familiar to focus on — and articles about prompt engineers provide something hopeful to look forward to.

But these things are not harbingers.

They’re not sources of any lasting orientation.

And they’re not grounded in the reality of the moment.

What, then, should schools of the future (by which I mean the schools of this fall) be explicitly designed to accomplish if they want to help today’s student navigate tomorrow’s world of unprecedented technological, ecological and ontological promise and peril?

There are a lot of possible answers, but here’s one that seems simple enough: Start focusing less on what we want kids to know and more on who we want them to become. And the good news is that lots of communities are already doing this — not by designing futuristic curricula or teaching kids how to be prompt engineers, but by recognizing that content is merely the means by which young people develop the skills and habits that can make them good neighbors and global citizens.

In our work with schools all over the world, this has become the thing we insist on. After all, if a school has yet to clearly identify which dispositions of the ideal graduate are most important — beyond basic literacy and numeracy — they cannot effectively impart any skills with consistency and certainty.

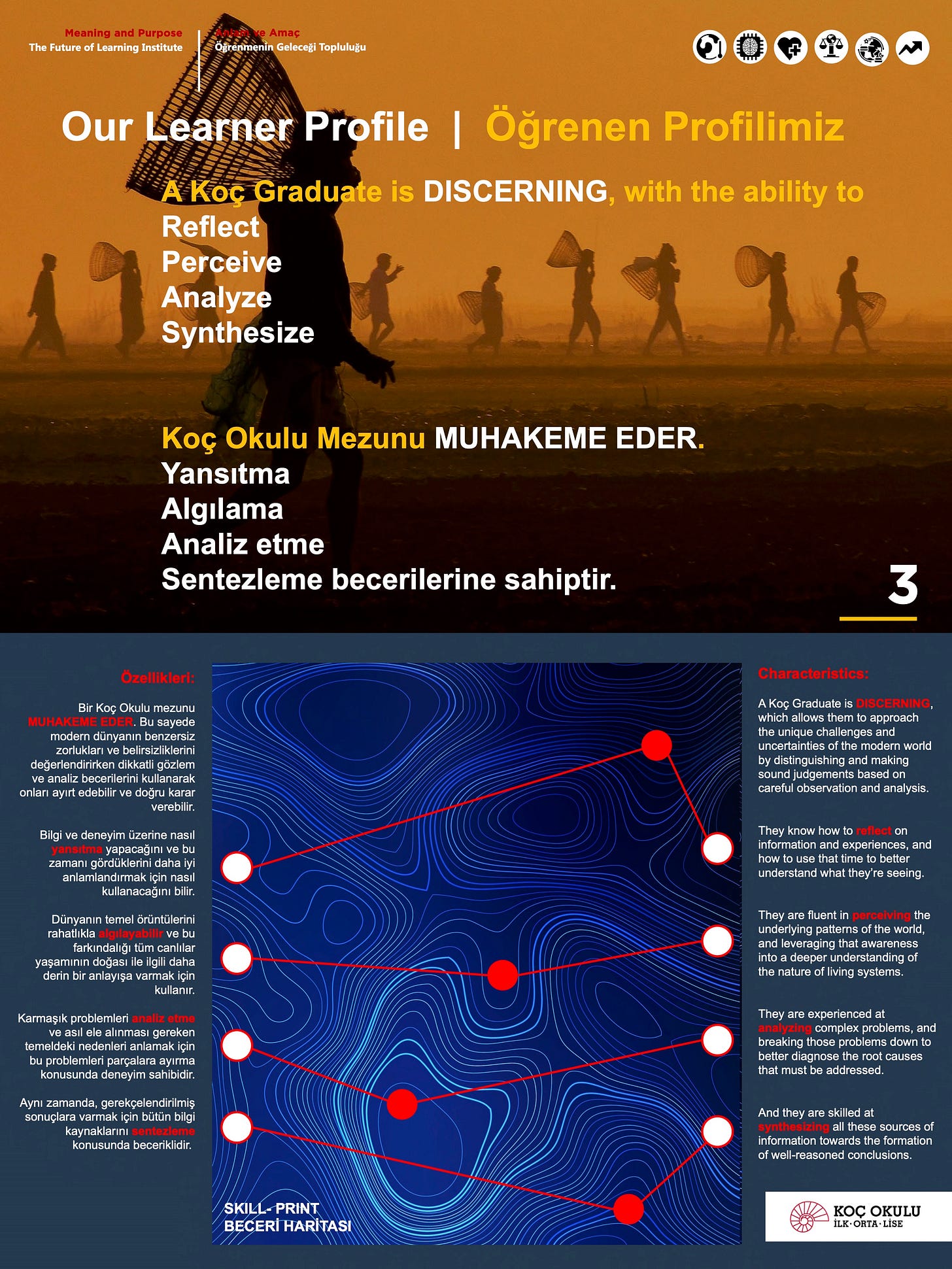

We just completed this process with the Koç School in Istanbul — a school whose innovative design I featured in a previous column. After many rounds of community input and conversation, Koç decided it was these five that mattered most:

-

Adaptation (the disposition of the global citizen)

-

Innovation (the disposition of the hand)

-

Discernment (the disposition of the mind)

-

Empathy (the disposition of the heart)

-

Integration (the disposition of the being)

As you can see, each disposition is connected to a specific set of sub-skills. Koç’s challenge as a school community is now to become even more intentional in the ways they allow young people to develop the sort of “skillprint” each disposition can engender.

The point is not for every school to adopt Koç’s framework, but to come up with its own — and to then to orient everything it does towards the cultural embodiment of those distinctly human qualities.

After all, in the end, our ability to become better humans may be the only lasting competitive advantage to which we can lay claim.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.