Larry Cuban on School Reform and Classroom Practice: High Performing Teachers with Low-Tech Classrooms

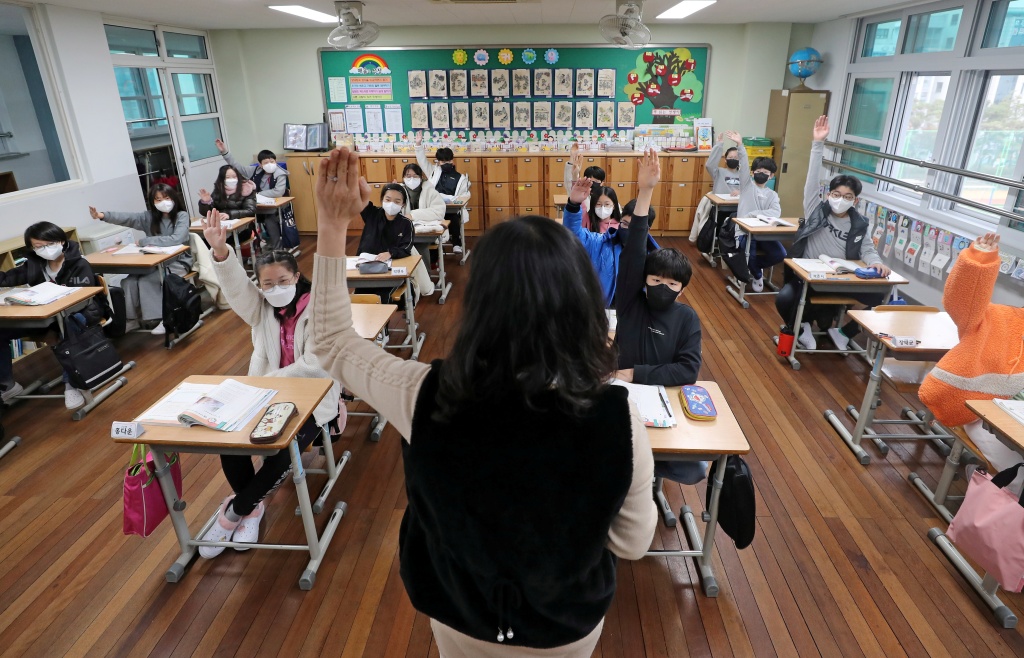

The title is neither a joke nor a poke in the eyes of techno-enthusiasts. Over a decade ago, journalist Amanda Ripley visited classrooms around the world and found that the best ones are low-tech. Specifically, she cited South Korea and Finland, countries that outscored the U.S. in international tests, as having low-tech classrooms. In South Korea, she quoted one student who described her room having a few old computers, an overhead projector, and few “new” technologies.

This March 2, 2021, photo shows children and a teacher having an in-person class while wearing face masks at an elementary school in Incheon, about 40 kilometers west of Seoul. (Yonhap)

A class in an elementary school in Gwangju holds a ceremony to welcome new students on Wednesday. (Yonhap)

Turn now to Finland, another country that Ripley mentioned. Finnish public schools have high tech devices available to students and teachers. Moreover, smart phones are common among children and youth across the socioeconomic spectrum. While Finland’s schools vary in use of devices, available photos show many low-tech classrooms.

Amanda Ripley quotes an expert on European schools about the lack of technological innovations in schools around the world:

“ ‘In most of the highest-performing systems, technology is remarkably absent from classrooms,’ says Andreas Schleicher, a veteran education analyst for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development who spends much of his time visiting schools around the world to find out what they are doing right (or wrong). ‘I have no explanation why that is the case, but it does seem that those systems place their efforts primarily on pedagogical practice rather than digital gadgets.‘ “

In the U.S., Ripley points out that when policymakers and politicians imagine schools and classrooms a decade from now “they often talk about a schoolhouse that looks like an Apple store, a utopia studded with computers, bathed in Wi-Fi, and wallpapered with interactive whiteboards.” Yet when Ripley visited a Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) school in Washington, D.C. she watched a veteran math teacher lead a fifth grade class through a lesson without a nod to the four idle computers in the rear of the room. When asked by Ripley, what would her perfect classroom be like, the teacher said: “If I were designing my ideal classroom, there’d be another body teaching. Or there’d be 36 hours in the day instead of 24.” No mention of laptops or hand-held devices or interactive white boards.

Ripley’s point and that of scores of other observers of first-rate teachers is that both low-tech and high-tech machines can surely help students learn but it is the teacher’s lesson objectives, knowledge of the subject, rapport with students, and a willingness to push and support them that count greatly in what students learn rather than anything intrinsic within the devices used.

Consider Direct Instruction–much of which occurs in KIPP schools–and a math lesson where the teacher uses an overhead projector, a low-tech tool that entered U.S. classrooms extensively in the 1930s. Nary a computer in sight. Direct Instruction gives progressives committed to student-centered instruction heartburn but its popularity among many teachers and administrators remains strong in low-income elementary schools, “Success for All” programs, Open Court Reading, and similar structured teaching strategies.

And what about those first-rate teachers whose students are surrounded by an abundance of laptops, interactive white boards, camcorders, flip video cameras, and a host of other devices? Those teachers still have to figure out the specific objectives for the next lesson, how to get students engaged, what activities will hit the desired objectives, and how will they know that students grasped those objectives. For these teachers sometimes the high-tech cornucopia gets in the way. Listen to a high school English teacher who is in a 1:1 laptop school (I am quoting Steve Davis, a San Jose Unified School District teacher, who I interviewed after I observed a lesson he taught):

Sometimes low-tech simply facilitates goals more effectively. Take a lesson on thesis statements for example. Each student has a thesis statement prepared (in theory) and is ready to share it with their group. I would love to use my blog for students to share and critique each other’s work, but it’s not the most logistically effective strategy. Marisol left her computer at home, Jordan can’t remember his password, and Justin can login but can’t seem to figure out how to post a comment. Sure, schools should be teaching these skills, but they’re not tested on the California Subject Tests. Technology integration has left technology instruction up to content teachers, while I learned the basics of computing in my sixth grade computer class. What’s my main goal? Teaching thesis. In this scenario, technology actually impedes my main goal instead of facilitating it. It’s much easier and more effective to get out the black markers and the butcher paper and have students make group posters and present them to the class. It’s not whiz-bang, but it gets the job done.

High performing teachers use high-tech and low-tech to engage and reach their students here and abroad. Not either-or. Unashamedly, I repeat a cliche that needs to be said again and again: Good teaching is not about access to and use of high-tech machines, it is about teachers knowing their subjects, establishing rapport with students, and prodding and supporting them to learn.

Ms. Garensha John leads a first-grade class at Capital Preparatory Harbor Lower School in Bridgeport, Conn.Credit…Christopher Capozziello for The New York Times

Kurt Russell, an experienced high school history teacher in Oberlin, Ohio, April 2022

A seventh-grade history class at the Atlanta Classical Academy, a charter school (David Walter Banks for The New York Times)

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.